An R reproducibility toolkit for the practical researcher > Day 1 > 01: What is reproducibilty anyway?

01: What is reproducibilty anyway?

By Paola Corrales and Elio Campitelli

This workshop will introduce some useful tools to help you write code that can be run anywhere with consistent results. We will focus on the practical aspects of reproducibility, but it’s still worth it to get some sense of what is reproducibility and what’s its aim.

What reproducibility is and what it is not

We will use “reproducibility” to talk about results that can be obtained by someone else given the same data and code. This is a technical problem. That a result is reproducible doesn’t mean that the result is scientifically valid, statistically sound or even that it’s computationally correct. Perfectly reproducible bugs are still bugs!

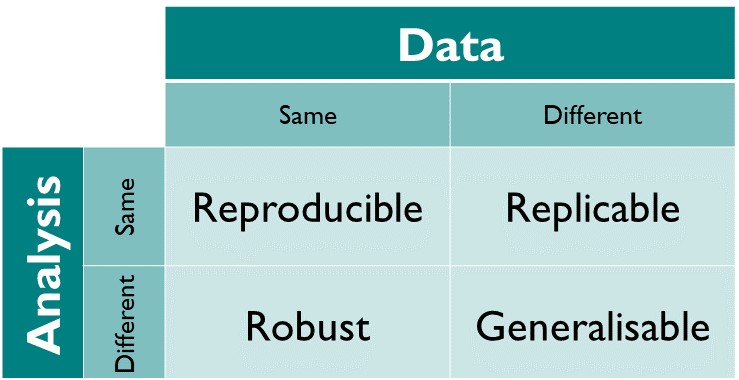

There are other related concepts, such as replicability, robustness and generalisability which relate to being able to reach the same results when changing data and/or methods. These are outside the scope of this workshop.

In summary, for a research finding to be reproducible both data and methods should be available and applying the described methods on the data lead to the same results.

Methods vs. code

In theory, method availability doesn’t necessarily mean code availability, but in practice it’s almost impossible to describe methods in such a way that enables full reproducibilty. As Ben Marwick wrote:

The problem is that most modern science is so complicated, and most journal articles so brief, it’s impossible for the article to include details of many important methods and decisions made by the researcher as [they] analyzed [their] data on [their] computer.

If good science can be irreproducible and reproducible results can be bad science, what’s the value of thinking about reproducibility?

The intent behind publishing results in science is to have the wider community understand them, check them, and build on top of them. Irreproducible research findings make each of these steps harder.

Lack of detailed methods can hinder other researchers' ability to correctly interpret the results. Methods sections usually describe only the big-picture steps and decisions, but are too short to explain every little detail of how the data was treated and can be ambiguous do the vagueness of human writing. But even in the case of sufficiently detailed explanations, there is no guarantee that they correctly describe the actual code or steps taken to reach the conclusions.

Without access to the actual code used to get numbers, tables and figures, it’s hard to spot and correct mistakes. For instance, in 2013 an influential 2010 economic report was found to contain technical errors, but only after three researchers got their hands into the actual excel spreadsheet that the original authors had used.

Finally, freely accessible code and data facilitates the other aspects of reproducible research. With access to data, other researchers can re-analyse it with other methods to check for robustness, and with access to code, they can apply the same methods to other, independent datasets to check for replicability.

The reproducibility spectrum

As with most things, reproducibility is non-binary. Having access to code and data sometimes is good, but how about describing the specific version of each software and packaged used? Do you need to describe the operating system? How about the architecture of the CPU?

How exact should results be to be considered successfully reproduced? Do we expect identical result bit by bit? Or do we allow for small changes in non-significant digits, cosmetic variation in figures such as fonts or colours?

For these reasons instead of saying that a research project is reproducible or not, is often more helpful to say that a research project is more or less reproducible and harder or easier to reproduce. A project that publishes code and data but not software versions is probably harder to reproduce than one that provides the virtual machine in which the code was run.

However, each “step” in the reproducibility spectrum requires additional skills and time. While some of those skills (such as, literal programming, version control, setting up environments) pay off in the long run, they can require a high up-front investment. This is made even harder in a collaborate setting in which not all members of the team are familiarised with the relevant techniques and technologies.

This workshop

In light of all this, the goal of this workshop is not to erect some perfect, pure standard of reproducibility that no researcher is able to attain, but to empower researchers to make their research as reproducible as they can (but not more). We don’t want anyone to feel ashamed for not using some piece of software, but to make then aware of all the cool and interesting tools than can streamline their research

Resources

Daniel Piqué: How I discovered a missing data point in a paper with 8000+ citations

useR! 2020: Keynote - Computational Reproducibility, from Theory to Practice (Anna Krystalli)